丙型肝炎失代偿期肝硬化患者死亡风险预测模型的建立及评价

DOI: 10.12449/JCH251216

Establishment and evaluation of a predictive model for the risk of death in patients with decompensated hepatitis C cirrhosis

-

摘要:

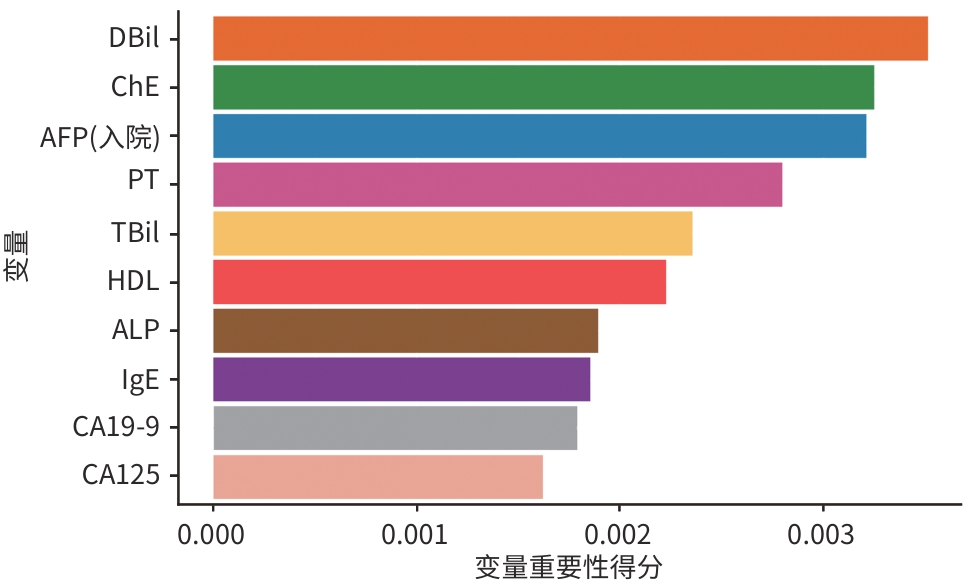

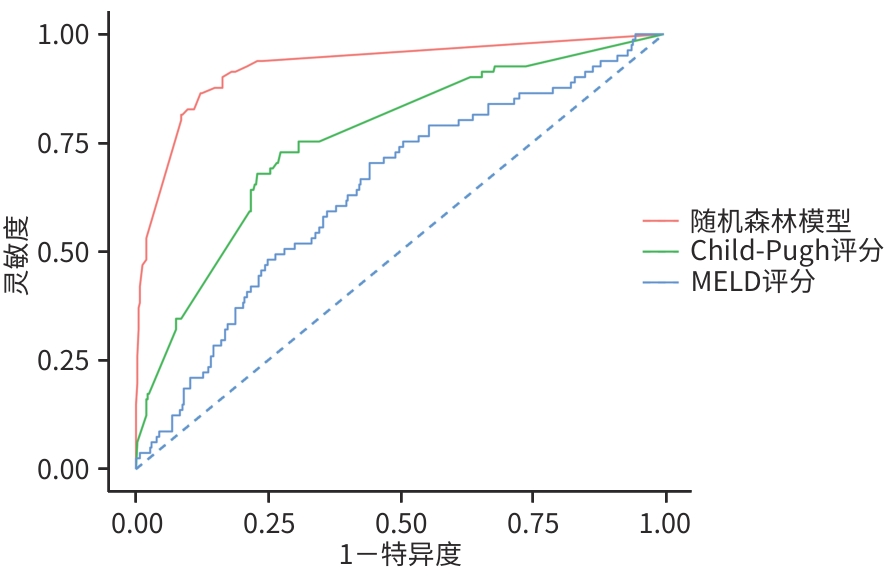

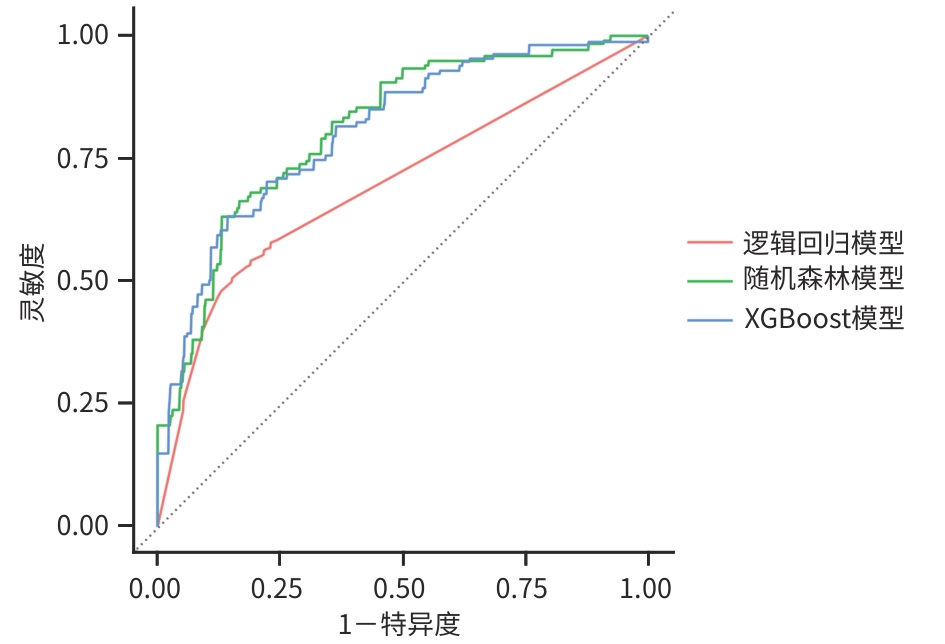

目的 基于机器学习算法构建丙型肝炎失代偿期肝硬化患者24个月死亡风险预测模型,并与传统的Child-Pugh评分和终末期肝病模型(MELD)评分进行比较。 方法 纳入2022年1月—2024年4月于昆明市第三人民医院住院的490例丙型肝炎失代偿期肝硬化患者,随访至2024年12月。根据随访期间患者的生存状态,分为死亡组(n=81)和生存组(n=409)。收集患者的人口学资料、合并症及临床生化指标。计量资料2组间比较采用成组t检验或Mann-Whitney U检验;计数资料组间比较采用χ2检验或Fisher精确概率法。通过逻辑回归模型、随机森林模型、XGBoost 3种模型对数据集进行训练,并采用10折交叉验证,绘制受试者操作特征曲线(ROC曲线),计算灵敏度、特异度、ROC曲线下面积(AUC)及召回率,以评估模型的预测能力。 结果 490例患者中男339例(69.2%)、女151例(30.8%),生存组与死亡组间合并肝脏恶性肿瘤、慢性肝衰竭、肝性脑病、艾滋病及低钙-低蛋白血症情况,以及腹水量及未接受药物治情况比较差异均有统计学意义(P值均<0.05)。在3种机器学习模型的预测能力评估中,随机森林模型的AUC最高(0.811),显著优于逻辑回归模型(0.676)和XGBoost模型(0.798);综合AUC和特异度,选择随机森林模型作为最佳预测模型。变量重要性分析显示,排名前10的变量(直接胆红素、胆碱酯酶、甲胎蛋白、凝血酶原时间、总胆红素、高密度脂蛋白胆固醇、碱性磷酸酶、免疫球蛋白E、糖类抗原19-9及糖类抗原125)对死亡风险预测贡献较高。通过ROC曲线及AUC对比随机森林模型、MELD评分和Child-Pugh评分对丙型肝炎失代偿期患者死亡风险的预测效能,结果显示随机森林模型的AUC区间跨度最小,稳定性显著优于传统评分。 结论 直接胆红素、胆碱酯酶、甲胎蛋白、凝血酶原时间、总胆红素、高密度脂蛋白胆固醇、碱性磷酸酶、免疫球蛋白E、糖类抗原19-9及糖类抗原125为丙型肝炎失代偿期肝硬化患者24个月死亡风险的特征变量。随机森林模型可显著提升该类患者死亡风险的预测效能,优于传统的Child-Pugh评分和MELD评分。 Abstract:Objective To construct a predictive model for the risk of 24-month mortality in patients with hepatitis C-related decompensated liver cirrhosis based on machine learning algorithms, and to compare this model with traditional Child-Pugh score and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score. Methods A total of 490 patients with hepatitis C-related decompensated liver cirrhosis who were hospitalized in The Third People’s Hospital of Kunming from January 2022 to April 2024 were enrolled and followed up to December 2024. According to the survival status of the patients during follow-up, they were divided into death group with 81 patients and survival group with 409 patients. Demographic data, comorbidities, and biochemical parameters were collected from all patients. The independent-samples t test or the Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparison of continuous data between two groups, and the chi-square test or the Fisher’s exact test was used for comparison of categorical data between groups. The Logistic regression model, the random forest model, and the XGBoost model were used for dataset training, and 10-fold cross validation was performed. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted, and sensitivity, specificity, area under the ROC curve (AUC), and recall rate were calculated to assess the predictive value of the model. Results Among the 490 patients, there were 339 male patients (69.2%) and 151 female patients (30.8%). There were significant differences between the survival group and the death group in the proportion of patients comorbid with malignant liver tumor, chronic liver failure, hepatic encephalopathy, AIDS or hypocalcemia/hypoproteinemia, as well as the amount of ascites and the proportion of patients without medication (all P<0.05). The assessment of the predictive ability of the three machine learning models showed that the random forest model had the largest AUC of 0.811, which was significantly better than that of the Logistic regression model (0.676) and the XGBoost model (0.798), and based on both AUC and specificity, the random forest model was selected as the optimal predictive model. The variable importance analysis showed that the top 10 variables (i.e., direct bilirubin, cholinesterase, alpha-fetoprotein, prothrombin time, total bilirubin, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, alkaline phosphatase, immunoglobulin E, carbohydrate antigen 19 - 9, and carbohydrate antigen 125) had relatively high contributions to predicting the risk of death. The ROC curve and AUC were used to compare the random forest model with MELD score and Child-Pugh score in terms of their ability to predict the risk of death in patients with hepatitis C-related decompensated liver cirrhosis, and the results showed that the random forest model had had the smallest AUC interval span, suggesting that this model had a significantly better stability than traditional scores. Conclusion Direct bilirubin, cholinesterase, alpha-fetoprotein, prothrombin time, total bilirubin, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, alkaline phosphatase, immunoglobulin E, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, and carbohydrate antigen 125 are characteristic variables for the risk of 24-month death in patients with hepatitis C-related decompensated liver cirrhosis. The random forest model can significantly improve the predictive efficacy of the risk of death in such patients, with a better performance than traditional Child-Pugh score and MELD score. -

Key words:

- Hepatitis C /

- Liver Cirrhosis /

- Prognosis /

- Machine Learning

-

表 1 HCV失代偿期肝硬化患者潜在死亡的基线资料统计表

Table 1. Baseline statistical table of potential mortality in patients with HCV decompensated cirrhosis

项目 生存组(n=409) 死亡组(n=81) 统计值 P值 性别[例(%)] χ2=6.884 0.009 男 273(66.7) 66(81.5) 女 136(33.3) 15(18.5) 住院时年龄(岁) 53(48~58) 52(48~58) Z=0.296 0.767 体重(kg) 63(55~70) 63(55~70) Z=-0.094 0.853 HCV基因分型[例(%)] 0.250 1b型 14(7.4) 2(5.9) 2a型 5(2.7) 0(0.0) 3a型 35(18.6) 11(32.4) 3b型 121(64.4) 21(61.8) 6型 13(6.9) 0(0.0) 肝硬化伴胃底静脉曲张[例(%)] 205(50.1) 35(43.2) χ2=1.293 0.256 肝脏恶性肿瘤[例(%)] 88(21.5) 39(48.1) χ2=24.975 <0.001 慢性肝衰竭[例(%)] 106(25.9) 30(37.0) χ2=4.170 0.041 肝性脑病[例(%)] 26(6.4) 16(19.8) χ2=15.482 <0.001 艾滋病[例(%)] 36(8.8) 15(18.5) χ2=6.845 0.009 慢性胃炎[例(%)] 34(8.3) 5(6.2) χ2=0.423 0.516 高血压[例(%)] 104(25.4) 18(22.2) χ2=0.372 0.542 2型糖尿病[例(%)] 106(25.9) 22(27.2) χ2=0.054 0.816 高尿酸血症[例(%)] 61(14.9) 6(7.4) χ2=3.228 0.072 甲状腺结节[例(%)] 31(7.6) 3(3.7) χ2=1.573 0.210 颈动脉斑块[例(%)] 12(2.9) 1(1.2) 0.704 胆总管结石[例(%)] 4(1.0) 1(1.2) >0.999 低钙-低蛋白血症[例(%)] 169(41.3) 44(54.3) χ2=4.650 0.031 肝硬度值[例(%)] 0.408 <7.3 kPa 31(18.2) 3(16.7) ≥7.3~9.3 kPa 11(6.5) 1(5.6) ≥9.3~14.6 kPa 22(12.9) 0(0.0) ≥14.6 kPa 106(62.4) 14(77.8) 腹水量[例(%)] χ2=6.555 0.038 小 94(61.0) 21(42.0) 中 43(27.9) 18(36.0) 大 17(11.0) 11(22.0) 未接受药物治疗[例(%)] 148(36.2) 40(49.4) χ2=4.979 0.026 MELD评分(分) 7.68(4.45~11.37) 10.73(7.48~14.42) Z=-3.981 <0.001 Child-Pugh评分(分) 8.00(7.00~9.00) 9.00(8.00~10.00) Z=-7.356 <0.001 注:HCV,丙型肝炎病毒;MELD,终末期肝病模型。

表 2 HCV失代偿期肝硬化患者潜在死亡的生化基线资料

Table 2. Biochemical baseline data of potential mortality in patients with HCV decompensated cirrhosis

项目 生存组(n=409) 死亡组(n=81) 统计值 P值 入院时HCV RNA阳性[例(%)] 139(34) 31(38) χ2=0.548 0.459 WBC(×109/L) 3.92(3.00~5.69) 4.68(3.21~5.92) Z=-1.697 0.141 NEUT(×109/L) 2.39(1.72~3.65) 3.13(1.89~4.52) Z=-2.654 0.016 NEUT%(%) 62.34±11.83 67.76±12.82 t=-3.474 <0.001 RBC(×1012/L) 3.83±0.97 3.29±1.00 t=4.375 <0.001 Hb(g/L) 118.09±34.29 106.59±33.45 t=2.778 0.006 PLT(×109/L) 83.00(58.50~121.00) 82.00(48.00~136.00) Z=0.037 0.962 PCT(L/L) 0.08(0.04~0.13) 0.10(0.06~0.14) Z=-2.428 0.028 TBil(μmol/L) 21.00(13.50~33.70) 33.80(18.40~68.50) Z=-4.273 <0.001 DBil(μmol/L) 8.50(5.30~14.90) 16.70(8.70~38.80) Z=-5.403 <0.001 IBil(μmol/L) 11.55(7.90~17.70) 14.60(8.20~25.70) Z=-2.703 0.007 ALT(U/L) 27.00(18.00~43.00) 31.00(23.00~55.00) Z=-2.120 0.032 AST(U/L) 40.00(28.00~66.00) 69.00(43.00~104.00) Z=-5.117 <0.001 TP(g/L) 64.90(57.90~72.00) 62.00(54.80~67.10) Z=3.181 0.002 Alb(g/L) 31.95(26.90~37.60) 25.70(22.10~29.70) Z=6.748 <0.001 PA(mg/L) 116.60(84.30~163.00) 75.40(55.80~111.90) Z=5.508 <0.001 GGT(U/L) 61.00(30.30~129.20) 103.00(39.90~196.00) Z=-2.672 0.003 ALP(U/L) 122.00(87.00~165.00) 148.00(99.00~221.00) Z=-3.305 <0.001 K+(mmol/L) 3.84(3.58~4.06) 3.77(3.50~3.98) Z=1.275 0.198 Na+(mmol/L) 139.70(137.70~141.20) 138.40(135.40~140.70) Z=2.955 0.003 CREA(μmol/L) 61.00(48.00~79.00) 62.00(46.00~75.50) Z=0.037 0.961 UREA(mmol/L) 4.63(3.58~6.37) 4.92(3.47~7.61) Z=-0.774 0.431 UA(μmol/L) 360.00(277.00~449.00) 358.50(288.00~439.50) Z=0.118 0.910 C1q(mg/L) 188.50(155.00~234.00) 168.50(140.00~210.00) Z=2.860 0.004 PT(s) 15.80(14.90~17.10) 17.50(15.60~19.90) Z=-4.854 <0.001 INR 1.34(1.22~1.53) 1.51(1.33~1.72) Z=-3.945 <0.001 TG(mmol/L) 0.87(0.65~1.29) 0.77(0.56~1.23) Z=1.852 0.052 CHOL(mmol/L) 3.31(2.58~4.20) 2.87(2.02~3.58) Z=3.427 <0.001 HDL-C(mmol/L) 0.93(0.64~1.22) 0.58(0.35~0.85) Z=6.112 <0.001 LDL-C(mmol/L) 1.84(1.38~2.35) 1.62(1.02~2.35) Z=1.756 0.073 Lpa(mg/L) 23.20(10.80~53.10) 17.10(6.55~54.45) Z=1.567 0.117 IgE(U/mL) 44.00(28.00~95.00) 66.00(33.00~337.00) Z=-4.284 0.003 IgA(g/L) 2.45(1.81~3.64) 3.24(2.53~4.58) Z=-4.330 0.002 T3(nmol/L) 1.65±0.51 1.46±0.45 t=2.206 0.032 T4(nmol/L) 93.91(75.33~114.18) 97.74(69.51~122.87) Z=0.748 0.788 FT3(pmol/L) 4.23±1.11 3.69±0.88 t=2.993 0.004 FT4(pmol/L) 14.52(12.64~16.43) 16.36(13.58~17.39) Z=-2.641 0.042 TSH(μIU/mL) 2.51(1.49~3.83) 2.45(1.60~3.45) Z=-1.110 0.853 CA125(U/mL) 29.16(13.69~128.44) 179.65(40.66~412.20) Z=-6.211 <0.001 CA15-3(U/mL) 13.32(9.18~19.82) 16.76(12.96~23.50) Z=-3.847 0.002 CA19-9(U/mL) 28.58(17.21~53.58) 49.76(21.29~77.67) Z=-4.217 0.001 AFP(ng/mL) 5.50(3.10~15.15) 9.45(3.49~611.55) Z=-3.340 0.003 LDH(U/L) 212.00(170.00~261.00) 266.00(209.00~348.00) Z=-5.113 <0.001 CEA 3.43(2.42~5.01) 4.70(3.05~7.21) Z=-4.191 <0.001 注:WBC,白细胞计数;NEUT,中性粒细胞绝对值;NEUT%,中性粒细胞百分比;RBC,红细胞计数;Hb,血红蛋白;HCT,红细胞压积;PLT,血小板计数;PCT,血小板压积;TBil,总胆红素;DBil,直接胆红素;IBil,间接胆红素;ALT,丙氨酸氨基转移酶;AST,天冬氨酸氨基转移酶;TP,总蛋白;Alb,白蛋白;PA,前白蛋白;GGT,γ-谷氨酰转移酶;ALP,碱性磷酸酶;UREA,尿素;CREA,肌酐;UA,尿酸;C1q,补体1q;PT,凝血酶原时间;INR,国际标准化比值;TG,甘油三酯;CHOL,总胆固醇;HDL-C,高密度脂蛋白胆固醇;LDL-C,低密度脂蛋白胆固醇;Lpa,脂蛋白a;Ig,免疫球蛋白;T4,甲状腺素;T3,三碘甲状腺素;FT4,游离甲状腺素;FT3,游离三碘甲状腺素;TSH,促甲状腺激素;CEA,癌胚抗原;LDH,乳酸脱氢酶;AFP,甲胎蛋白;CA125,糖类抗原125;CA15-3,糖类抗原15-3;CA19-9,糖类抗原19-9。

表 3 3种机器学习模型的预测能力评估

Table 3. Evaluation of the predictive power of three machine learning models

模型 AUC 灵敏度 特异度 阳性预测值 召回率 逻辑回归模型 0.676 0.518 0.817 0.341 0.518 随机森林模型 0.811 0.141 0.984 0.733 0.141 XGBoost模型 0.798 0.257 0.966 0.257 -

[1] Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators. Global change in hepatitis C virus prevalence and cascade of care between 2015 and 2020: A modelling study[J]. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2022, 7( 5): 396- 415. DOI: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00472-6. [2] World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report 2024: Action for access in low- and middle-income countries[R/OL]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240090562. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240090562 [3] TAN DJH, SETIAWAN VW, NG CH, et al. Global burden of liver cancer in males and females: Changing etiological basis and the growing contribution of NASH[J]. Hepatology, 2023, 77( 4): 1150- 1163. DOI: 10.1002/hep.32758. [4] Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of hepatitis C(2022 edition)[J]. Chin J Infect Dis, 2023, 41( 1): 29- 46. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn311365-20230217-00045.中华医学会肝病学分会, 中华医学会感染病学分会. 丙型肝炎防治指南(2022年版)[J]. 中华传染病杂志, 2023, 41( 1): 29- 46. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn311365-20230217-00045. [5] YANG J, RAO HY. Epidemiological trends and treatment benefits of hepatitis C virus infection in China[J]. Clin Medicat J, 2021, 19( 12): 6- 11. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-3384.2021.12.002.杨甲, 饶慧瑛. 中国丙型病毒性肝炎流行趋势及治疗获益[J]. 临床药物治疗杂志, 2021, 19( 12): 6- 11. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-3384.2021.12.002. [6] ASRANI SK, DEVARBHAVI H, EATON J, et al. Burden of liver diseases in the world[J]. J Hepatol, 2019, 70( 1): 151- 171. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.014. [7] MURPHY SL, XU JQ, KOCHANEK KD, et al. Deaths: Final data for 2018[J]. Natl Vital Stat Rep, 2021, 69( 13): 1- 83. [8] WANG SB, CHEN JH, JIE R, et al. Natural history of liver cirrhosis in South China based on a large cohort study in one center: A follow-up study for up to 5 years in 920 patients[J]. Chin Med J, 2012, 125( 12): 2157- 2162. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2012.12.014. [9] CÁRDENAS A, GINÈS P. Management of patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation[J]. Gut, 2011, 60( 3): 412- 421. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2009.179937. [10] D’AMICO G, GARCIA-TSAO G, PAGLIARO L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: A systematic review of 118 studies[J]. J Hepatol, 2006, 44( 1): 217- 231. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.10.013. [11] LU JJ, XU AQ, WANG J, et al. Direct economic burden of hepatitis B virus related diseases: Evidence from Shandong, China[J]. BMC Health Serv Res, 2013, 13: 37. DOI: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-37. [12] ALONSO LÓPEZ S, MANZANO ML, GEA F, et al. A model based on noninvasive markers predicts very low hepatocellular carcinoma risk after viral response in hepatitis C virus-advanced fibrosis[J]. Hepatology, 2020, 72( 6): 1924- 1934. DOI: 10.1002/hep.31588. [13] National Health Commission. Work plan for eliminating the public health hazards of hepatitis C( 2021— 2030)[EB/OL].( 2021-08-31)[ 2025-02-10]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s3586/202109/c462ec94e6d14d8291c5309406603153.shtml?R0NMKk6uozOC=1654310439640. http: //www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s3586/202109/c462ec94e6d14d8291c5309406603153.shtml?R0NMKk6uozOC=1654310439640国家卫生健康委员会. 消除丙型肝炎公共卫生危害行动工作方案( 2021— 2030 年)[EB/OL].( 2021-08-31)[ 2025-02-10]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s3586/202109/c462ec94e6d14d8291c5309406603153.shtml?R0NMKk6uozOC=1654310439640. http: //www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s3586/202109/c462ec94e6d14d8291c5309406603153.shtml?R0NMKk6uozOC=1654310439640 [14] BRUDEN DJT, MCMAHON BJ, TOWNSHEND-BULSON L, et al. Risk of end-stage liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver-related death by fibrosis stage in the hepatitis C Alaska Cohort[J]. Hepatology, 2017, 66( 1): 37- 45. DOI: 10.1002/hep.29115. [15] JIN YH, CHEN WC, YAN S. The ratio of liver size to abdominal area evaluates the prognosis of 85 patients with decompensated cirrhosis[J]. Chin J Dig, 2017, 37( 8): 547- 549. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-1432.2017.08.008.金月红, 陈卫昌, 严苏. 肝脏面积与腹部面积比评估肝硬化失代偿期患者85例的预后[J]. 中华消化杂志, 2017, 37( 8): 547- 549. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-1432.2017.08.008. [16] MCDONALD SA, INNES HA, ASPINALL E, et al. Prognosis of 1169 hepatitis C chronically infected patients with decompensated cirrhosis in the predirect-acting antiviral era[J]. J Viral Hepat, 2017, 24( 4): 295- 303. DOI: 10.1111/jvh.12646. [17] WEI L, XIE HZ, WENG JB, et al. Risk factors and pathogenic characteristics of nosocomial infections in patients with decompensated cirrhosis[J]. Chin J Nosocomiology, 2017, 27( 21): 4842- 4845. DOI: 10.11816/cn.ni.2017-170695.韦玲, 谢会忠, 翁敬飚, 等. 失代偿期肝硬化患者医院感染危险因素及病原学特点探讨[J]. 中华医院感染学杂志, 2017, 27( 21): 4842- 4845. DOI: 10.11816/cn.ni.2017-170695. [18] SHEN LJ, WU LB, XIONG XQ, et al. Analysis of the influence factors for the prognosis of the patients with HCV-related decompensated cirrhosis[J/CD]. Chin J Clin(Electron Ed), 2013, 7( 20): 9121- 9125. DOI: 10.3877/cma.j.issn.1674-0785.2013.20.027.申力军, 吴立兵, 熊小青, 等. 失代偿期丙型肝炎肝硬化患者预后影响因素分析[J/CD]. 中华临床医师杂志(电子版), 2013, 7( 20): 9121- 9125. DOI: 10.3877/cma.j.issn.1674-0785.2013.20.027. [19] NIU Q. Evaluation value of end-stage liver disease model score combined with NLR on short-term prognosis of decompensated liver cirrhosis[D]. Yanji: Yanbian University, 2021.牛琦. 终末期肝病模型评分联合NLR对失代偿期肝硬化短期预后的评估价值[D]. 延吉: 延边大学, 2021. [20] XIGU RG, SU Y, TONG J, et al. Application of model for end-stage liver disease score in end-stage liver disease[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2025, 41( 3): 556- 560. DOI: 10.12449/JCH250325.希古日干, 苏雅, 佟静, 等. 终末期肝病模型(MELD)评分在终末期肝病中的应用[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2025, 41( 3): 556- 560. DOI: 10.12449/JCH250325. -

PDF下载 ( 1416 KB)

PDF下载 ( 1416 KB)

下载:

下载: