非酒精性脂肪性肝病合并幽门螺杆菌感染患者肠道菌群特征分析

DOI: 10.12449/JCH250511

Features of intestinal flora in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and Helicobacter pylori infection

-

摘要:

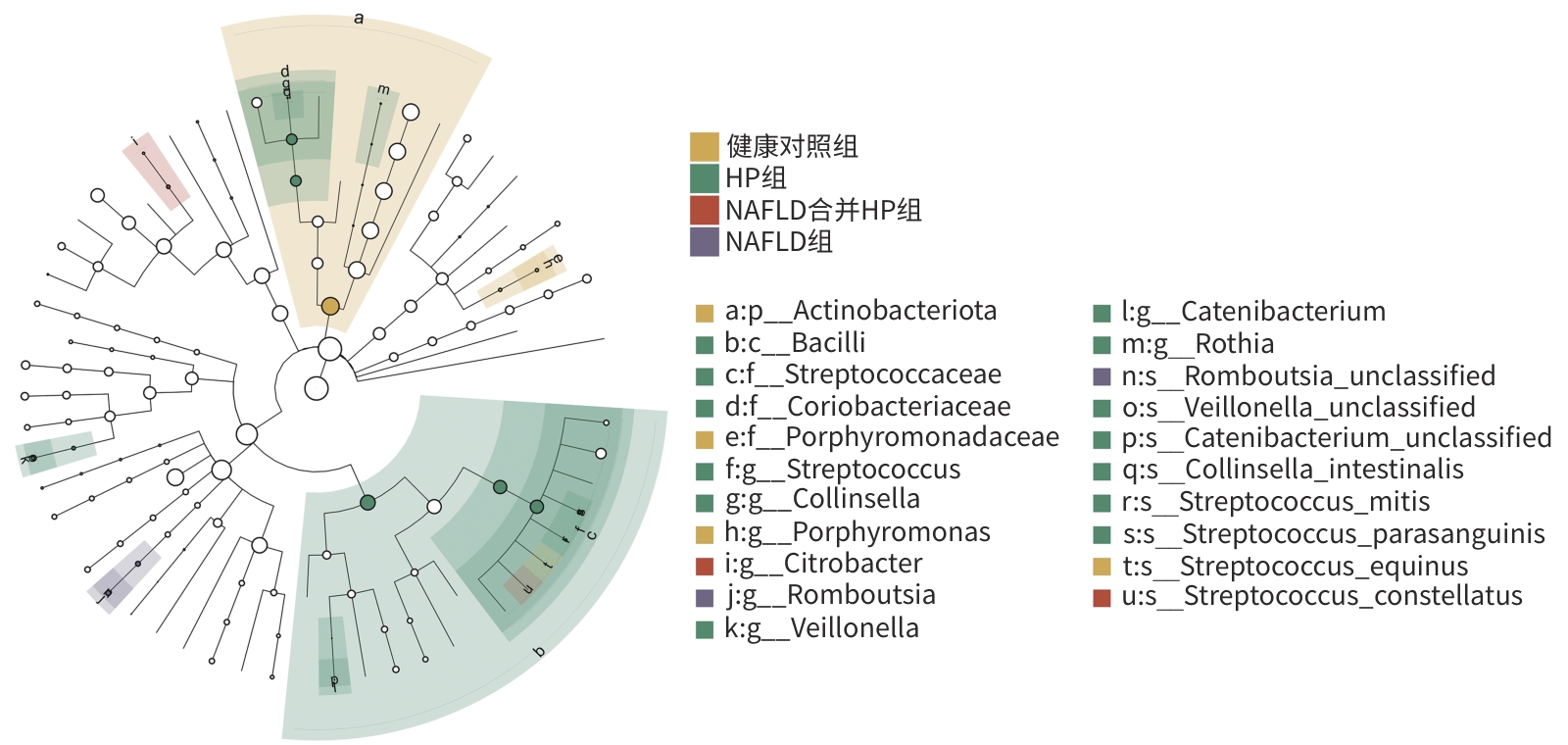

目的 通过比较健康人群、幽门螺杆菌(HP)感染患者、非酒精性脂肪性肝病(NAFLD)患者以及HP感染合并NAFLD患者的肠道菌群变化特点,探讨NAFLD合并HP患者肠道菌群特征及作用机制。 方法 选取河南科技大学第二附属医院2023年3月1日—2024年4月30日收治的NAFLD患者19例(NAFLD组)、HP感染患者19例(HP组)、NAFLD合并HP感染患者19例(NAFLD合并HP组),另选取健康体检者20例作为对照。留取粪便标本,提取标本的总DNA,进行PCR扩增,通过16S rDNA测序,分析4组人群肠道菌群特征及差异性。计量资料多组间比较采用方差分析,计数资料多组间比较采用χ2检验。菌群物种之间差异性分析采用Mann-Whitney U检验或Kruskal-Wallis H检验。 结果 NAFLD合并HP组与其他3组相比,肠道菌群丰富度有降低趋势。NAFLD合并HP组与NAFLD组相比、NAFLD组与健康对照组相比,菌群分布具有明显差异性(P值均<0.05)。在门水平上,NAFLD合并HP组占前3位的物种分别为厚壁菌门(59.94%)、变形菌门(17.00%)、放线菌门(14.75%),相比于其他3组,变形菌门占比增加,放线菌门占比减少。在属水平上,NAFLD合并HP组的前5位优势菌属分别为Bifidobacterium、Streptococcus、Escherichia-Shigella、Agathobacter、Ruminococcus gnavus_group。与NAFLD组相比,NAFLD合并HP组Streptococcus、Veillonella、Rothia的丰度升高,Dialister、Ruminococcus toraues_group的丰度降低。与HP组相比,NAFLD合并HP组Collinsella、Subdoligranulum、Catenibacterium、Porphyromonas的丰度降低,而Citrobacter、Olsenella的丰度升高,物种差异性分析均具有统计学意义(P值均<0.05)。 结论 NAFLD合并HP感染患者的肠道菌群发生相应变化,这些菌群可能是HP感染促进NAFLD发生、发展的肠道微生态因素。 Abstract:Objective To investigate the features and mechanism of action of intestinal flora in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and Helicobacter pylori (HP) infection by comparing the changes in intestinal flora between the healthy population, the patients with HP infection, the patients with NAFLD, and the patients with NAFLD and HP infection. Methods This study was conducted among the 19 patients with NAFLD (NAFLD group), 19 patients with HP infection (HP group), and 19 patients with NAFLD and HP infection (NAFLD+HP group) who were admitted to The Second Affiliated Hospital of Henan University of Science and Technology from March 1, 2023 to April 30, 2024, and 20 individuals undergoing physical examination were enrolled as control group. Fecal samples were collected, total DNA was extracted for PCR amplification, and 16S rDNA sequencing was performed to compare the features of intestinal flora between the four groups. An analysis of variance was used for comparison of continuous data between multiple groups, and the chi-square test was used for comparison of categorical data between multiple groups. The Mann-Whitney U test or the Kruskal-Wallis H test was used for comparison of the species in intestinal flora. Results The NAFLD+HP group showed a tendency of reduction in flora abundance compared with the other three groups. There was a significant difference in flora distribution between the NAFLD+HP group and the NAFLD group and between the NAFLD group and the control group (P<0.05). At the phylum level, the top three species in the NAFLD+HP group were Firmicutes (59.94%), Proteobacteria (17.00%), and Actinobacteria (14.75%), with an increase in the proportion of Proteobacteria and a reduction in the proportion of Actinobacteria compared with the other three groups. At the genus level, the top five dominant bacteria in the NAFLD+HP group were Bifidobacterium, Streptococcus, Escherichia-Shigella, Agathobacter, and Ruminococcus gnavus_group. Compared with the NAFLD group, the NAFLD+HP group had increases in the abundance of Streptococcus, Veillonella, and Rothia and reductions in the abundance of Dialister and Ruminococcus toraues_group. Compared with the HP group, the NAFLD+HP group had reductions in the abundance of Collinsella, Subdoligranulum, Catenibacterium, and Porphyromonas and increases in the abundance of Citrobacter and Olsenella (all P<0.05). Conclusion Patients with NAFLD and HP infection have changed in intestinal flora. These flora may be the intestinal microecological factors for HP infection in promoting the development and progression of NAFLD. -

表 1 4组研究对象一般情况比较

Table 1. Comparison of the general conditions of the four groups of study subjects

项目 NAFLD组(n=19) NAFLD合并HP组(n=19) HP组(n=19) 健康对照组(n=20) 统计值 P值 男/女(例) 11/8 9/10 10/9 11/ 9 χ2=0.456 0.928 年龄(岁) 42.57±8.12 41.63±7.86 42.42±8.28 40.75±8.72 F=0.202 0.895 ALT(U/L) 37.68±9.92 37.95±8.34 34.05±7.34 31.35±6.07 F=3.019 0.035 AST(U/L) 27.16±7.76 25.74±7.11 25.74±6.39 23.85±8.29 F=0.652 0.584 GGT(U/L) 30.42±7.52 27.90±6.72 30.16±6.30 27.70±6.11 F=0.904 0.443 BMI(kg/m2) 25.56±1.46 25.63±1.70 23.44±1.96 22.79±1.07 F=16.564 <0.001 -

[1] FANG J, YU CH, LI XJ, et al. Gut dysbiosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapeutic implications[J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2022, 12: 997018. DOI: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.997018. [2] ZHANG YB, GUO GY, ZHENG CH, et al. Research progress in association between Helicobacter pylori and metabolic syndrome and its effect on occurrence and development of metabolic syndrome[J]. J Jilin Univ(Med Edit), 2024, 50( 6): 1757- 1762. DOI: 10.13481/j.1671-587X.20240631.张艳彬, 郭光业, 郑彩华, 等. 幽门螺杆菌与代谢综合征关联性及其对代谢综合征发生发展影响的研究进展[J]. 吉林大学学报(医学版), 2024, 50( 6): 1757- 1762. DOI: 10.13481/j.1671-587X.20240631. [3] ABO-AMER YE, SABAL A, AHMED R, et al. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease(NAFLD) in a developing country: A cross-sectional study[J]. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes, 2020, 13: 619- 625. DOI: 10.2147/DMSO.S237866. [4] OKUSHIN K, TSUTSUMI T, IKEUCHI K, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and liver diseases: Epidemiology and insights into pathogenesis[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2018, 24( 32): 3617- 3625. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i32.3617. [5] Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical Association. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of metabolic dysfunction-associated(non-alcoholic) fatty liver disease(Version 2024)[J]. J Prac Hepatol, 2024, 27( 4): 494- 510.中华医学会肝病学分会. 代谢相关(非酒精性)脂肪性肝病防治指南(2024年版)[J]. 实用肝脏病杂志, 2024, 27( 4): 494- 510. [6] KONING M, HERREMA H, NIEUWDORP M, et al. Targeting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease via gut microbiome-centered therapies[J]. Gut Microbes, 2023, 15( 1): 2226922. DOI: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2226922. [7] ZHANG DY, WANG Q, BAI FH. Bidirectional relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Insights from a comprehensive meta-analysis[J]. Front Nutr, 2024, 11: 1410543. DOI: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1410543. [8] MANTOVANI A, LANDO MG, BORELLA N, et al. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and risk of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: An updated meta-analysis[J]. Liver Int, 2024, 44( 7): 1513- 1525. DOI: 10.1111/liv.15925. [9] THURSBY E, JUGE N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota[J]. Biochem J, 2017, 474( 11): 1823- 1836. DOI: 10.1042/BCJ20160510. [10] LEVY M, KOLODZIEJCZYK AA, THAISS CA, et al. Dysbiosis and the immune system[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2017, 17( 4): 219- 232. DOI: 10.1038/nri.2017.7. [11] BOURSIER J, MUELLER O, BARRET M, et al. The severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with gut dysbiosis and shift in the metabolic function of the gut microbiota[J]. Hepatology, 2016, 63( 3): 764- 775. DOI: 10.1002/hep.28356. [12] MAVILIA-SCRANTON MG, WU GY, DHARAN M. Impact of Helicobacter pylori infection on the pathogenesis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease[J]. J Clin Transl Hepatol, 2023, 11( 3): 670- 674. DOI: 10.14218/JCTH.2022.00362. [13] GAO JJ, ZHANG Y, GERHARD M, et al. Association between gut microbiota and Helicobacter pylori-related gastric lesions in a high-risk population of gastric cancer[J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2018, 8: 202. DOI: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00202. [14] NABAVI-RAD A, SADEGHI A, ASADZADEH AGHDAEI H, et al. The double-edged sword of probiotic supplementation on gut microbiota structure in Helicobacter pylori management[J]. Gut Microbes, 2022, 14( 1): 2108655. DOI: 10.1080/19490976.2022.2108655. [15] DU LJ, CHEN BR, CHENG FL, et al. Effects of Helicobacter pylori therapy on gut microbiota: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Dig Dis, 2024, 42( 1): 102- 112. DOI: 10.1159/000527047. [16] WANG YH, HUANG Y. Effect of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium bifidum supplementation to standard triple therapy on Helicobacter pylori eradication and dynamic changes in intestinal flora[J]. World J Microbiol Biotechnol, 2014, 30( 3): 847- 853. DOI: 10.1007/s11274-013-1490-2. [17] WEISS G, FORSTER S, IRVING A, et al. Helicobacter pylori VacA suppresses Lactobacillus acidophilus-induced interferon beta signaling in macrophages via alterations in the endocytic pathway[J]. mBio, 2013, 4( 3): e00609-12. DOI: 10.1128/mBio.00609-12. [18] AHN SB, JUN DW, KANG BK, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of a multispecies probiotic mixture in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease[J]. Sci Rep, 2019, 9( 1): 5688. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-019-42059-3. [19] den BESTEN G, van EUNEN K, GROEN AK, et al. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism[J]. J Lipid Res, 2013, 54( 9): 2325- 2340. DOI: 10.1194/jlr.R036012. [20] YOON SJ, YU JS, MIN BH, et al. Bifidobacterium-derived short-chain fatty acids and indole compounds attenuate nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by modulating gut-liver axis[J]. Front Microbiol, 2023, 14: 1129904. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1129904. [21] BLAAK EE, CANFORA EE, THEIS S, et al. Short chain fatty acids in human gut and metabolic health[J]. Benef Microbes, 2020, 11( 5): 411- 455. DOI: 10.3920/BM2020.0057. [22] MBAYE B, MAGDY WASFY R, BORENTAIN P, et al. Increased fecal ethanol and enriched ethanol-producing gut bacteria Limosilactobacillus fermentum, Enterocloster bolteae, Mediterraneibacter gnavus and Streptococcus mutans in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis[J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2023, 13: 1279354. DOI: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1279354. [23] CROST EH, COLETTO E, BELL A, et al. Ruminococcus gnavus: Friend or foe for human health[J]. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 2023, 47( 2): fuad014. DOI: 10.1093/femsre/fuad014. -

PDF下载 ( 6646 KB)

PDF下载 ( 6646 KB)

下载:

下载: